Historical Images from Disrupting Time

Jacques David shown later in life (public domain). David is the main character in Disrupting Time and also wrote what became known as the David Report. He was an unsuspected industrial spy (in the modern sense of the word) and admitted to sneaking into the Waltham Watch factory incognito in the fall of 1876.

Theo Gribi shown later in life (public domain). Gribi went to the Centennial Exhibition as a judge for the Swiss delegation. However, he soon was joined by Jacques David where the two became industrial spies, acquiring the secrets of the American watch industry.

Royal Robbins, about the age/time he purchased Waltham in 1857. At the time, he was 33 years old. (Public domain)

Royal Robbins, shown later in life, treasurer and chief executive of the Waltham Watch Co at the time of its targeting by the Swiss watch industry (Public domain)

The woman on the far right of this photo (looking at the cameria) is Eliza Jane Putnam, who is brought to life in chapter 3 of the book. Thank you to my friend Wayne McCarthy, president of the Waltham Historical Society, who sleuthed and discovered this photo of Putnam. She is shown here in 1885 at another World's Fair representing Waltham.

Eliza Jane Putnam, who is brought to life in chapter 3 of the book. Thank you to my friend Wayne McCarthy, president of the Waltham Historical Society, who sleuthed and discovered this photo of Putnam. She is shown here in 1885 at another World's Fair representing Waltham.

The Main Building from the Centennial Exhibition. Notice the white Civil War statue out front. You have probably seen one of these before in your hometown. This sculpture debuted at the Centennial and became ubiquitous in America (Centennial Photographic Company)

Inside the Main Building of the Centennial Exhibition. The scale and vastness are hard to comprehend (Centennial Photographic Company)

This is the site of the Main Building then-and-now. The orchestra platform is not the site of this overgrown fountain. You can visit the site in Fairmount Park in Philiadelphia (author's photo/compilation).

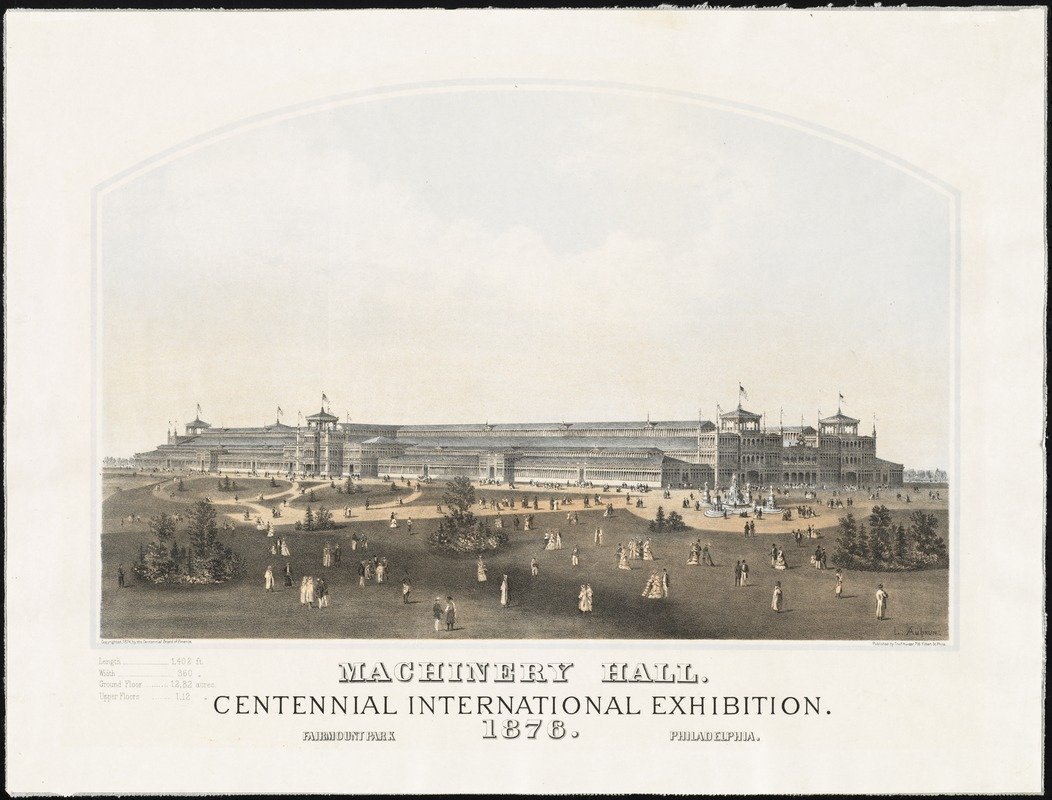

A full view of Machinery Hall. It was a vast palace devoted to industry. (Public domain)

The lake at the Centennial Exhibition. Machinery Hall is the building in the background (public domain)

The Corliss steam engine from the 1876 Centennial Exhibition. It was "a site to behold, a site for a lifetime." (public domain, Centennial Photographic Company)

The monorail debuted at the Centennial Exhibition. A photo of it here shows the elevated railway going across the grounds. (Public domain)

View of Machinery Hall. Waltham's exhibit can be seen with a small booth with 3 white windows at the base of the Corliss engine (public domain, Centennial Photographic Company)

The Waltham exhibit in Machinery Hall. This is the exhibit that initially drew Gribi's attention. It sits just feet from the large Corliss Steam Engine - not shown in this photo (public domain, Centennial Photographic Company)

Believe it or not, this is what the site of Waltham's exhibit in Machinery Hall at the Centennial looks like today. Where you see the log in the middle of the pond, that was the approximate site of Waltham's Machinery Hall assembly line exhibit. The hall was taken down and turned into a drainage pond shortly after the conclusion of the Centennial. (Author's photo)

Waltham's exhibit in the Main Building featuring 2,200 watches. It was marveled by Eduard Favre Peret, the Swiss judge.

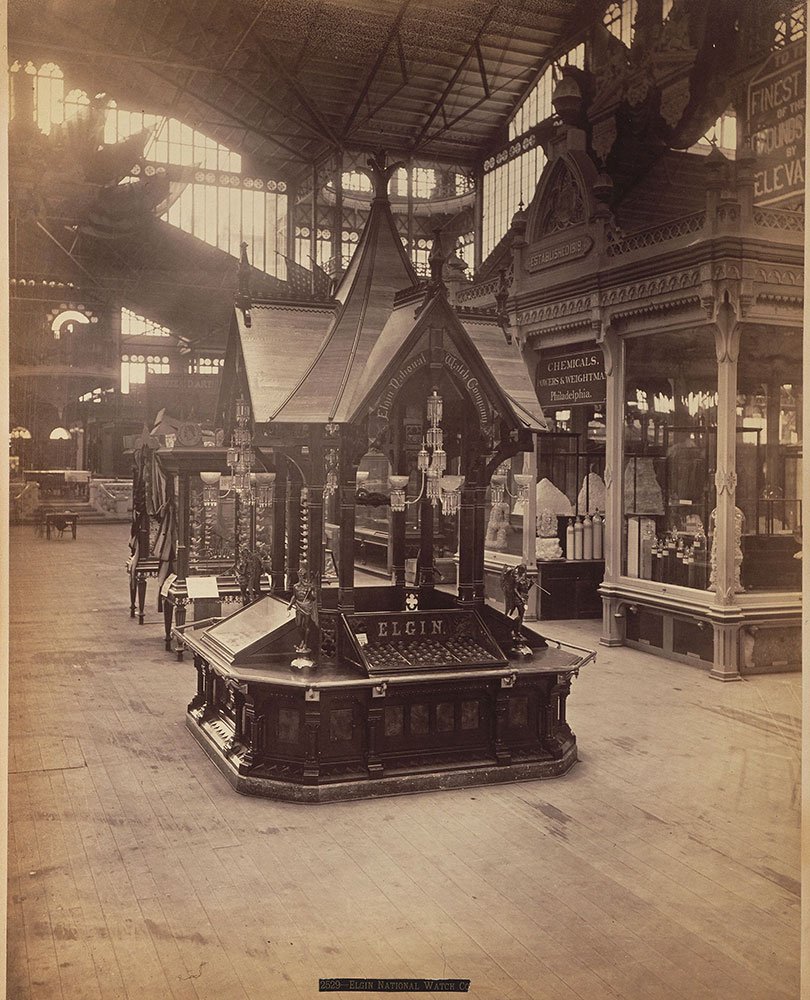

The Elgin National Watch Company's exhibit in the Main Building of the Centennial Exhibition (Centennial Photographic Company)

An aerial view of the Centennial Exhibition as seen from a hot air balloon. (Public domain).

Map of the Centennial grounds (public domain)

One of the few Centennial Exhibition buildings that remain today - now the Please Touch Museum in Philadelphia (author's photo)

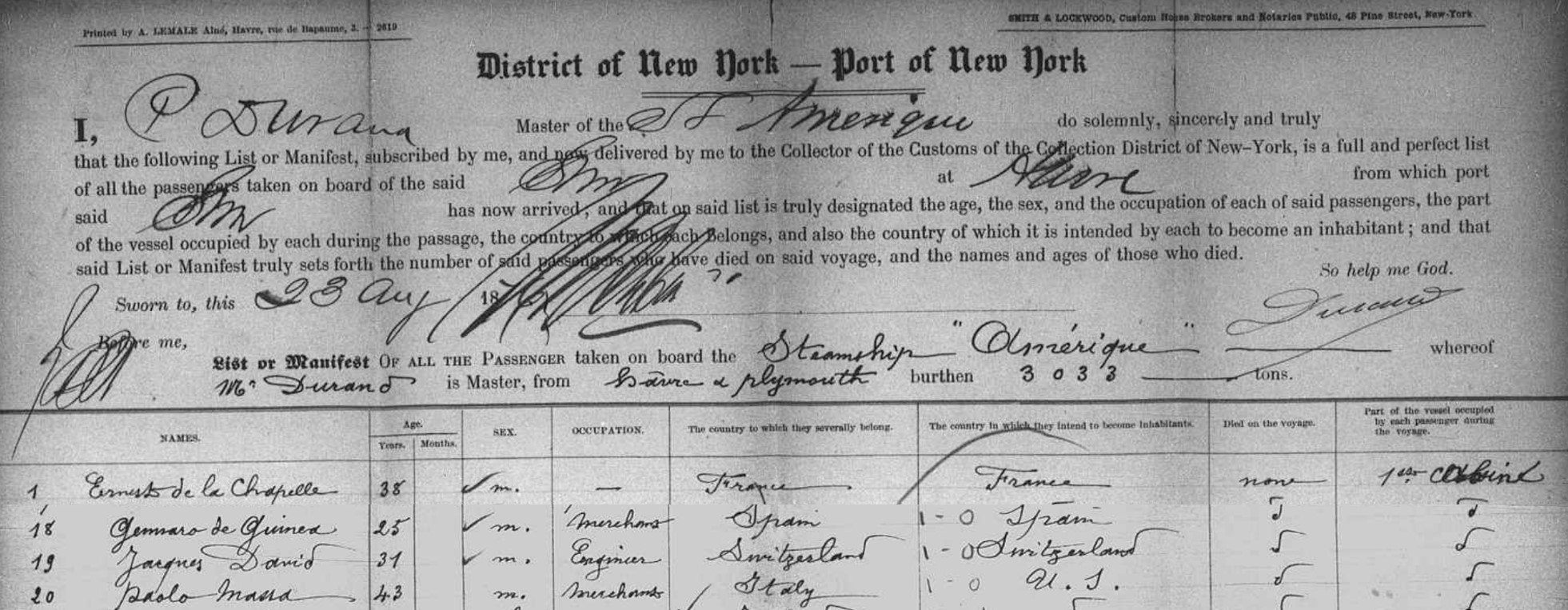

Manifest document for arrival into New York, showing Jacques David's arrival (public domain)

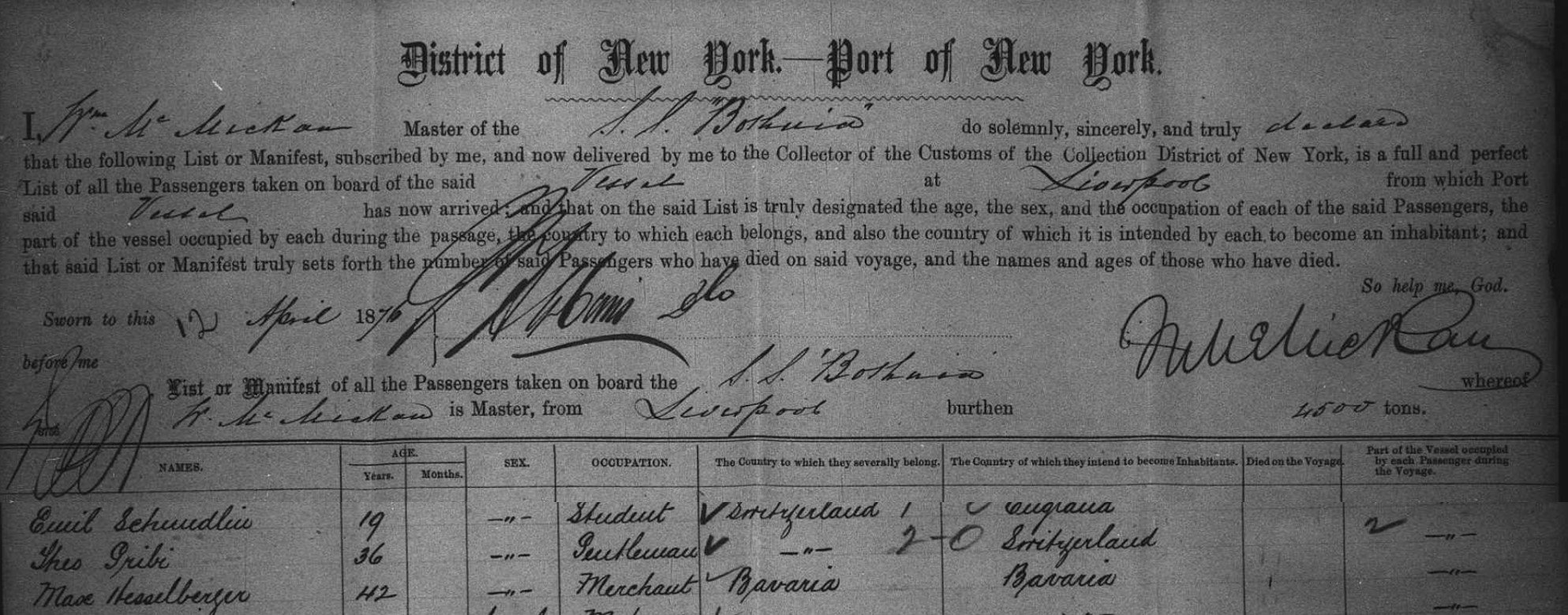

Theo Gribi's arrival into New York (public domain)

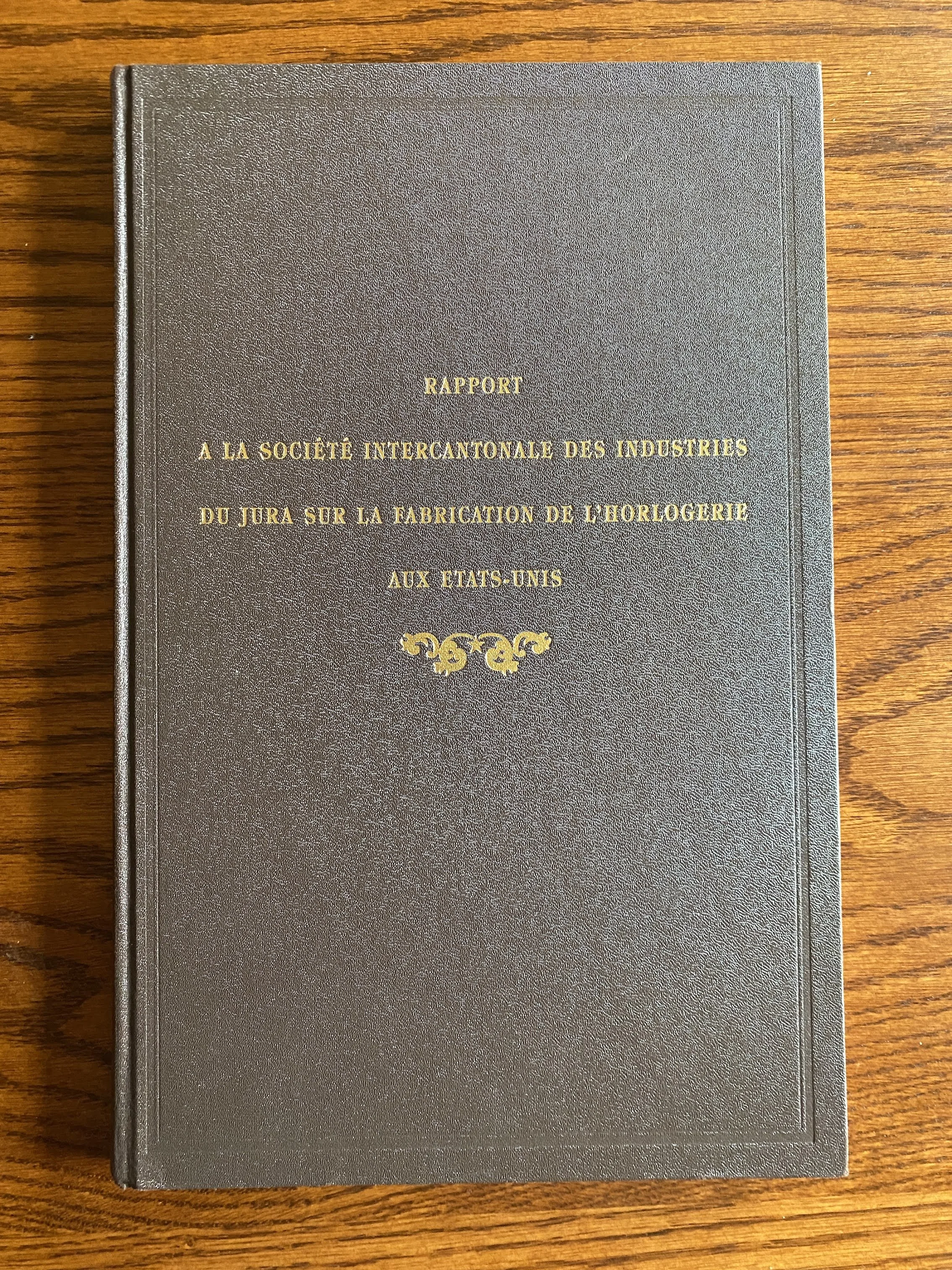

Jacques David's report (special edition facsimile copy produced in 1992 by Longines - Author's photo)

Photo of a Swiss river valley showing factories quaintly lined up across the valley. Circa 1890. (Library of Congress, Public Domain).

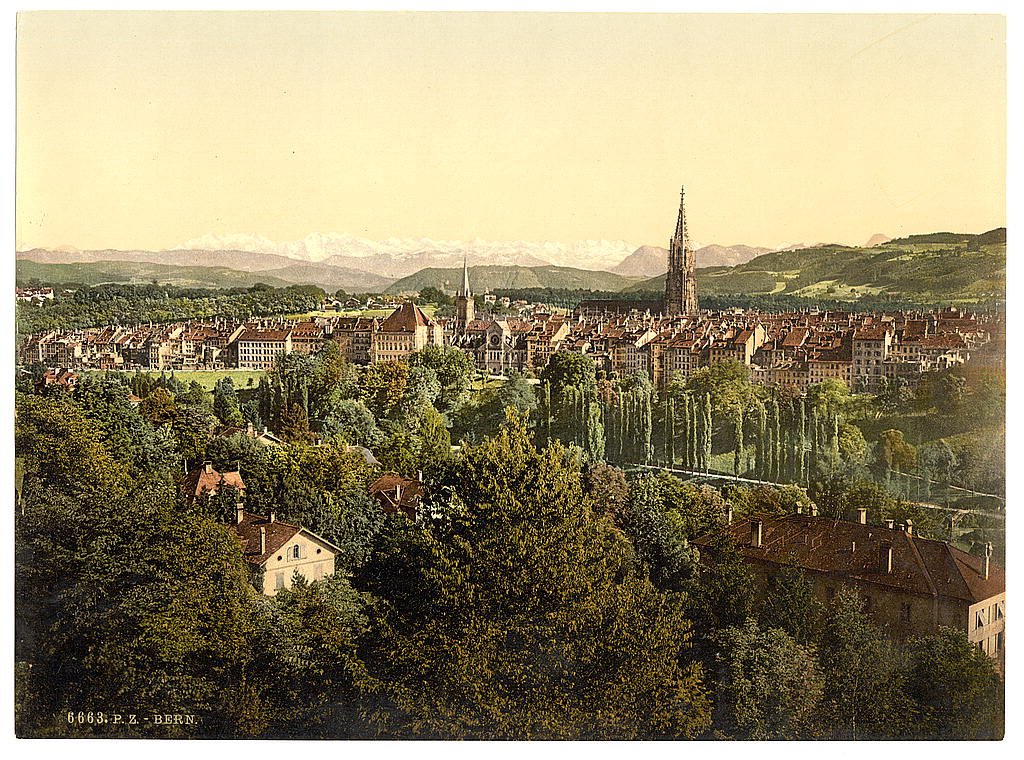

City of Bern, which would become a watchmaking center following David's report. Much of the watchmaking migrated to cities like Bern where they needed a concentration of workers to fill factories. Circa 1890. (Public Domain, Library of Congress).

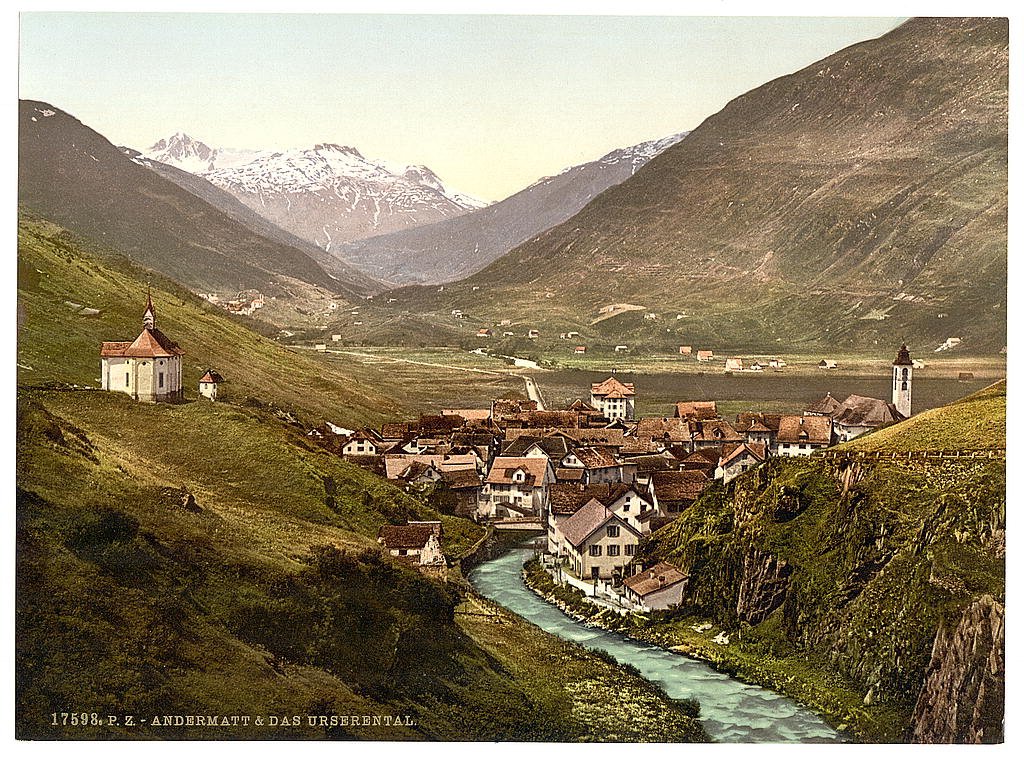

Swiss mountain regions, very similar to what is described for where many watchmakers and farmers lived and worked. Circa 1890. (Public Domain, Library of Congress).

City of Solothurn, which would become a watchmaking center following David's report. Much of the watchmaking migrated to cities like Solothurn and Bern where they needed a concentration of workers to fill factories. Circa 1890. (Public Domain, Library of Congress).

The first Waltham factory building, from 1854, 3 years before Robbins would purchase the company. (Public domain)

Early Waltham factory, around the time of Robbins' purchase of the company in 1857. (courtesy of the Waltham Historical Society - click the photo to visit their site, Public domain)

An etching of the Waltham factory in 1858, one year after Robbins purchased the company. (Public domain)

Waltham Factory circa 1870 (public domain)

Waltham factory as it appears today (Author's photo)

Waltham factory probably around 1890-1900 (note the powerlines) showing well-manicured streets and frontage (courtesy of the Waltham Historical Society - click the photo to visit their site, Public domain)

Inside the Waltham factory around the time of David's visit. Provided courtesy of the American Watchmaker-Clockmakers Institute collection - click the photo to visit their site. (from the stereographic photo collection by L. Lewis, public domain)

Inside the Waltham factory around the time of David's visit. Provided courtesy of the American Watchmaker-Clockmakers Institute collection - click the photo to visit their site. (from the stereographic photo collection by L. Lewis, public domain)

Inside the Waltham factory around the time of David's visit. Provided courtesy of the American Watchmaker-Clockmakers Institute collection - click the photo to visit their site. (from the stereographic photo collection by L. Lewis, public domain)

Inside the Waltham factory circa 1893 (public domain)

Women workers of Waltham inside the factory, probably in the 1870s or 1880s. It appears they are celebrating a wedding. (courtesy of the Waltham Historical Society - click the photo to visit their site, Public domain)

Workers inside the Waltham factory circa 1893. Notice the bright light and ubiquitous windows. (Public domain)

Inside the Waltham factory circa 1890. (Public domain).

A surprise to many, but Waltham had a day nursery for working mothers. Women made up 40% of the workforce. This photo is from circa 1910. (Waltham, Public domain)

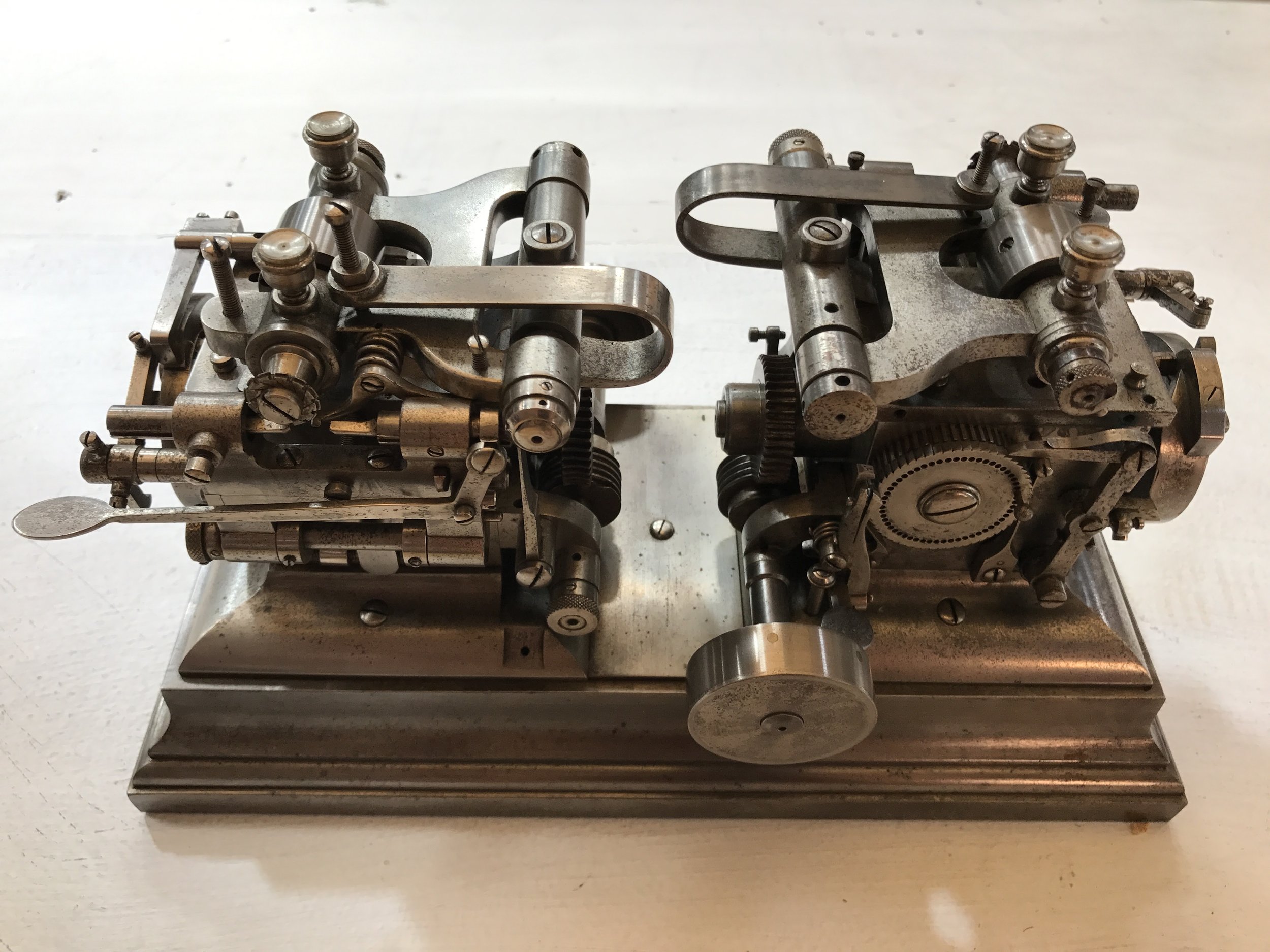

A Webster-Marsh pinion cutting machine. One of these was operated by Eliza Jane Putnam at the Centennial Exhibition and she would have been seen by David and Gribi. (Author's photo)

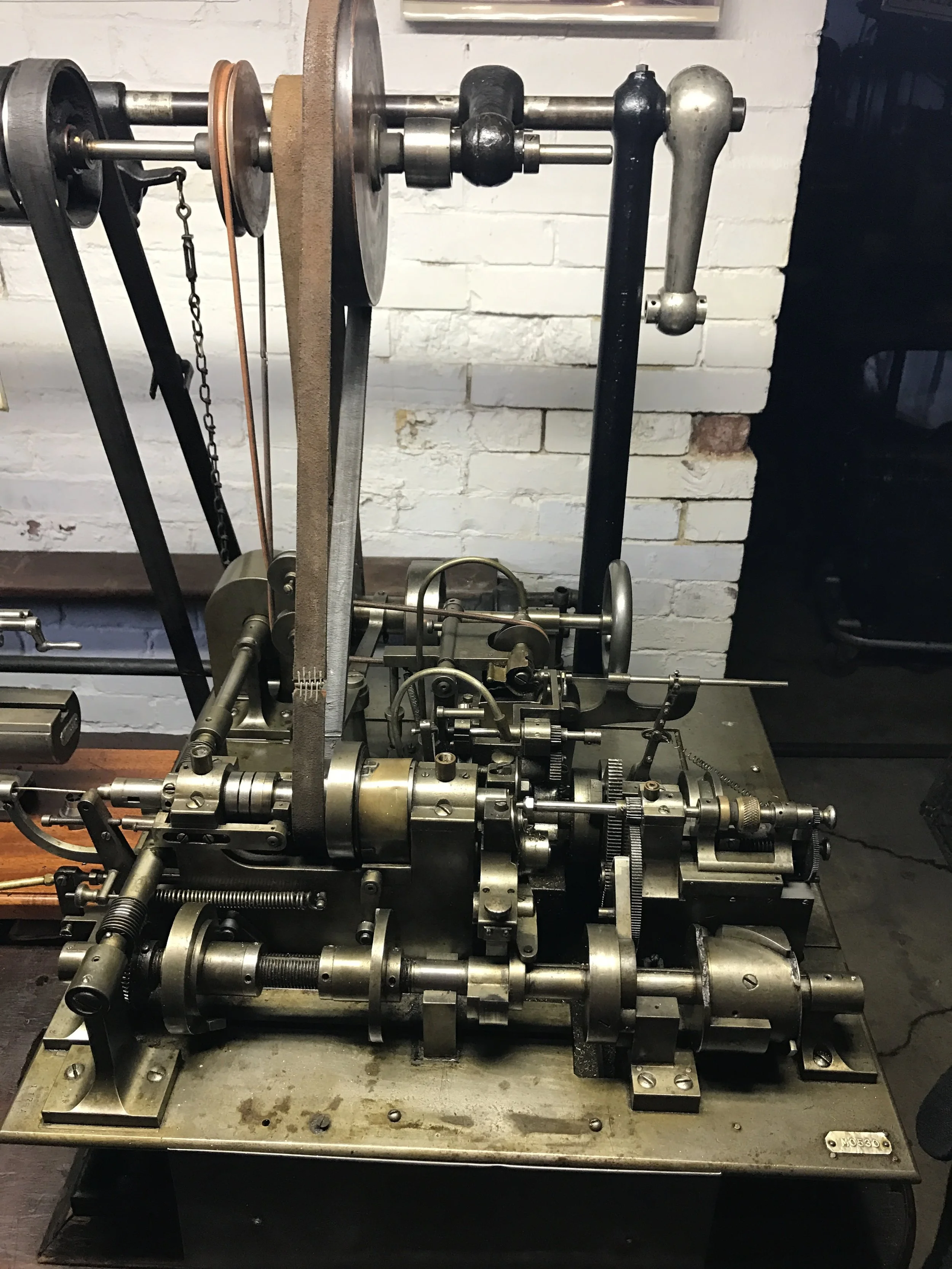

The automatic screw machine marveled by Gribi, now owned by a collector. The chromed pieces on the top part indicate this particular machine (or parts of it) may have even been one of those actually seen by Gribi at the Centennial. Click the image to see a video of the machine in action. (Author's photo)

These tiny screws are the output of the automatic screw machine. They are tedious to make by hand but critical to watchmaking. The screw-machine introduced a step change in automated production, making it possible to produce a screw every 5 seconds. (Author's photo)

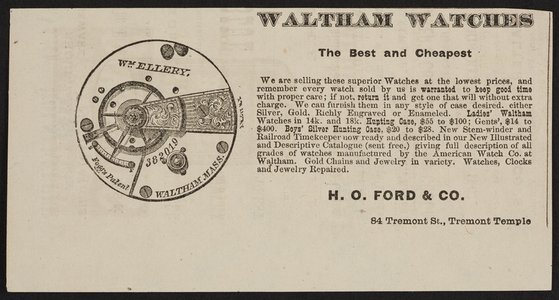

Waltham advertisement from the late 19th century. It emphasizes Waltham's market positioning approach of cheap and reliable. This became a strategic folly as the market evolved and Waltham could not change it's positioning due to the competition and choices of the Swiss. (Public domain)